Through this book, one will be able to envisage the travails of an ascetic litterateur whose large inner world and obscure existence governed his work.

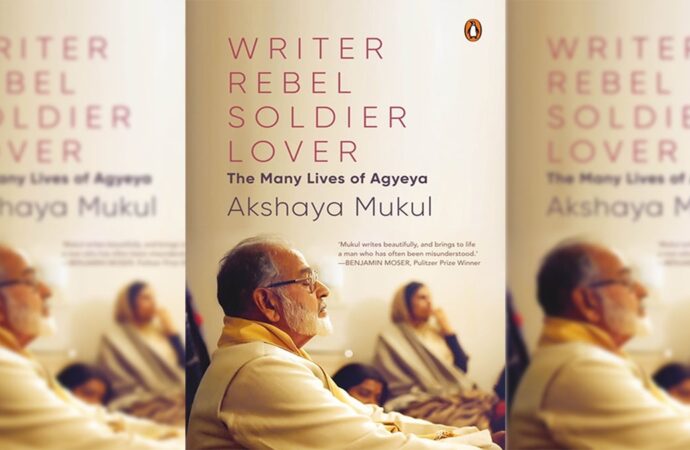

I found Akshay Mukul’s Writer, Rebel, Soldier, Lover: The Many Lives of Agyeya while I was looking for some non-conformist individualist literature in Indian literary universe after completing Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse last year. The enormous tome meticulously records many lives of a stalwart litterateur who was the first polymath and polyglot of Hindi literary world. Mukul has covered the minutiae of Agyeya’s life in 565 pages of biography and 200 pages of reference material. The author has laboriously sifted all the pulsating facets of his life from his collection of private papers. He had accessed these papers with the help of Vasudha, Agyeya’s last partner Ila’s sister. The several years of labour in sieving information from the papers in twenty trunks, few cartons, and two almirahs is evident in this humungous volume.

The author has divided the entire book into five parts and has very humanely illustrated various phases of his life with no room for boredom or ennui in any chapter. The initial chapters describe influence of his father’s library in shaping his challenging classical style of writing and his college education that taught him nuances of John Galsworthy, T.S Elliot, and DH Lawrence, Tagore etc and made his opus radical humanist yet not Marxist. The book contains interesting accounts of young Vatsayan entering the non-Brahmin hostel at Madras Christian College, his obfuscations in court while defending the case for himself in Delhi Conspiracy Case and becoming the sole spokesperson of the accused group, his fiery romantic notes for Kripa Sen during his Army soujourn, and the conceptualization of path breaking Taar Saptak(High Septet) anthology series.

Literary Career

The book describes Agyeya’s literary journey meticulously from early prison days to his ground reporting of the Bihar’s drought at Dinaman magazine. His literary voyage started sometimes in 1932 during his incarceration days when Jainendra took two of his stories to Premchand who published both stories in Jagran after passing them through the tough standards he had set for the publication. Jainendra had become a conduit for him for the outer world. By late 1932, he had written nearly seven stories with Vipathga on the verge of completion. All these stories contained the sombre scientific and experimental synthesis from the literary works of Galsworthy, Trostsky, Alexander Kuprin, Boris Pilnayk etc. After publishing Bhagnadoot, his identity was revealed and he drew attention from great authors of Hindi literary world.

With Vishwapriya, Agyeya entered into a fiery debate with romanticists or chayawadi stalwarts as they thought that his work contained overtly complex metaphysical thoughts and was obscene. His critically acclaimed works such as Shekhar – Ek Jiwani and Nadi Ke Dwip also received the similar reviews in the form of utmost praise or extreme vilification in the literary cahoots. I am thankful to this book as it revealed to me these outstanding gems of Hindi prose. The book also revealed to me the allure of metaphysical poetry compilations of Agyeya such as Hari Ghaas Par Shan Bhar, Pehle Main Sannata Bunta Hoon, Indradhanush Ye Raunde Hue etc. The author has also explored the humane side of Agyeya for writers in the form of instances where he formed a trust for writers with the money he received from the Jnanpith Award and when he attends funeral of Muktibodh with his wife Kapila.

Women in Agyeya’s Life

Agyeya’s inclination for women germinated through the disbelief of his mother on him in his large male dominated household. Hence, he saw a considerate mother in women such as Miriam Benade, Ellen Roy, Indumati, and Santosh who with sober sensitivity used to put everything in order. He was emotionally involved with a cousin, married twice, and associated with his last partner till death. Although very considerate for women till adulthood, his unremorseful indifference for women such as Santosh, Kripa, and Kapila appears almost patriarchal and is painful to read. However, the author has described his association with all these women with great compassion. Agyeya visibly was inclined towards independent women and had a great disbelief in the fundamental premise of Indian marriage where only husband provided.

One of the many triumphs of this book is the chapter related to Agyeya’s association with Kripa Sen during early 1940s. Kripa was struggling with her divorce at that time, was extremely well-read, witty, and having lost both her parents had become a gypsy. From the earliest letters, she was hopelessly smitten with him and equated her love with lines from East Coker by T.S Elliot and sometimes addressed him Vatsyayanaavitch. He too was madly in love with her because of her deftness with British literature, wit, and her giving names to people. Once in his letters, he signed off as ‘Yours (Boiling with rage, green with jealously and mad with impotent anger).’ Later, he immortalised Kripa as his protagonist Rekha in Nadi ke Dwip when she got married to Rao. All the while going through these chapters, I wondered how a man so much in love with an intelligent and vivacious woman like Kripa can leave her.

The book is replete with many such contrarieties of Agyeya’s life. It also describes the turbulence in his life because of him being an extremely individualist person and his highly nuanced self. However, the accounts of associations with his father, MN Roy, and Mathilisharan Gupt are other significant fetes of this book. Despite his several fellowship travels to foreign countries, teaching stint at Berkeley, lectures for Sahitya Akademy, and editing of English periodicals such as Thought and Vak, he was able to produce an unparalleled existential and psychoanalytic work such as Nadi Ke Dwip. The book is also a pure delight for those who wish to the understand the gradual development of modern and progressive writing in Hindi literature with the contribution of writers such as Jainendra, Nemichandra, Prabhkar Machwe, Ram Vilas Sharma, Muktibodh, Shamsher Bahadur Singh, and Phanishwar Nath Renu. Therefore, through this book one will be able to envisage the travails of an ascetic litterateur whose large inner world and obscure existence governed his work more than the circumstances outside.