God men from spiritual industry have got a strong bashing from the litterateurs since antiquity. This does not infer that no serious god men were portrayed in Indian English fiction.

The 14th century English poet Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, a story book mostly in verses is still read with relish. It gives a representation of the contemporary society and ill-practices thriving in it through witty and humorous couplets. Churchmen in Chaucer’s time were known to be corrupt. Describing the lifestyle of a monk, Chaucer writes,

“He was an easy man in penance-giving.

Where he could hope to make a decent living.

But strong enough to butt a bruiser down

He knew the taverns well in every town

And every innkeeper and barmaid too

Better than lepers, beggars and that crew.”

In our country too, the priests and god men have been the butt of ridicule. In early Indian English literature, we have the inimitable G.V. Desani. His classic novel All About Hatterr on the basis of unconventional, extravagant witty prose can be claimed as a precursor of Salman Rushdie’s style of writing. The Eurasian protagonist of this novel, Hindustanwala Hatterr has strange predicaments after he lands in India. He arrives in the search of spiritual enlightenment and meets seven gurus known for their specialization in various spiritual fields but each meeting turns into an adventure that disillusions him further.

Thereafter, Hatterr goes to interview the ‘Sage of Wilderness’ as reporter of a newspaper to get guidance about meditative practice (tapasya). The sage is known for it and indeed appears to be so. He is very thin and bony, whereas his disciple is well-built and burly. The Guru demands some offering (dakshina) in advance when Hatterr requests the sage to utter some words of wisdom. However, Hatterr was hypnotized for surrendering all that he had in return for that mere a towel! It came as a revelation for him later that the two members of the ashram were brothers dealing in old clothes. They were based in Lucknow and this was their ingenious way to collect stock. All the saints portrayed in this novel happen to be charlatans of this kind.

“Canst thou, my nephew, spare me thy trousers, thy jacket, thy shirt, thy shoes, thy cuff-links, thy watch, every accessory thou hast on thy person? Speak if thou wilt. Before I could say for what old (sic) how, the disciple approached me spontaneously, with a dirty towel in his hand, bearing the orange textile imprint of India’s G.I.P. Railway, fully expecting of me a post-haste denuding!” (52).”

Similarly, Rohinton Mistry in his book A Fine Balance portrays a character called Bal Baba. The word ‘Bal’ is actually baal in Hindi which means a strand of hair. This unconventional hermit accepts hair as his alms. Being a barber in the past, he collects and sells it further. How a guru can achieve the tag of a spiritually omnipotent mystic is beautifully described in R.K. Narayan’s Guide. In this book, the protagonist is mistaken for a guru because of his dress. In Khushwant Singh’s novel Burial at the Sea, we find a female guru riding a tiger evoking rebellion for patriarchy among the readers.

The flourishing religious industry of these days have led to emergence of self-styled godmen such as Asa Ram, Ram Rahim, Virendra Dikshit, Ram Pal etc which have been booked under crimes heinous as rape and murder. Hence, such god men from spiritual industry have got a strong bashing from the litterateurs since antiquity. This does not infer that no serious god men were portrayed in Indian English fiction. One such instance is found in Anita Desai’s novel Journey to Ithaca. In this book, an Italian named Matteo and his German wife Sophie take lessons in spirituality from an Indian female guru whom they refer as mother. Matteo never falters in practising meditation the way mother has taught him. The relentless pursuit of his self-ordained goal eventually pays off.

“Then, as he continued to gaze at it, he saw that what was perfectly balanced there in a cleft in the tree was not a stone at all but a circle, and it contained within it another circle, and another, that there was no beginning and no end to them; they were infinite; there were infinity. […] and to his dazzled eyes they revolved within each other and yet remained perfectly static, maintaining a total balance and harmony that could be divine.”

Sophie wasn’t convinced about the capabilities of mother despite her long stay in the aashram. She scrutinizes the past of this hermit only to reveal her journey as a dancer who later renounced the world. The story depicts two facets of faith. In the first aspect of faith Matteo succeeds; whereas Sophie fails to have the glimpse of the divine in the second.

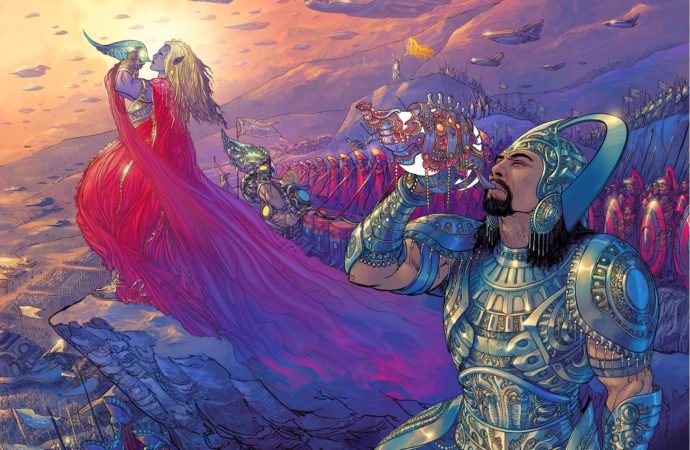

Let’s now talk about mythical folklores of gods and goddesses. Our epics serve as a great repertoire of stories for the present-day novelists. They narrate these stories in their characteristic way which may or may not be near the original version. The re-illustration of these haloed mythical tales into exotic form has become a lucrative venture for the tribe of such authors. Therefore, such texts are on increase like never before. Beginning with Ashok Banker who has some fifty novels to his credit based on myths, there is a long list of practitioners of this art.

Here is an instance from Banker’s Siege of Mithila, one of his early works. Sita is a braveheart who excels in martial arts and is responsible for saving Ram and Lakshman from the clutches of robbers in a jungle. Manthara practices voodoo and is placed in Ayodhya by Ravana whom she can invoke anytime. She even transforms a serving girl into Kaikeyi which nearly naked ‘brushes against the guards’. The guards could only infer that the queen had taken more of ‘soma than she could hold.’

Lord Shiva is seen addicted to smoking marijuana despite warnings in Amish Tripathi’s The Immortals of Meluha, one of the books in his series called Shiva trilogy. He is an ignorant and diffident tribal chieftain and does not know the meaning of the sacred word ‘Aum’. Nandi is not a mythical bull acting as the vehicle of the god but rather Shiva’s guru who enlightens him about the meaning of Aum. The city of Ayodhya surpasses the most organized societies of Europe in this world as we come across both young and old trying to woo whomever they fancy for. Authors who wish to present a different perspective of an epic that lies suppressed in the original text have also emerged.

The Palace of Illusions by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni narrates Mahabharata from Draupadi’s part. The perspective presented is the new narrative is clearly a feminist one in which Draupadi’s relationship with Krishna and Karna is highlighted. Karna’s Wife by Kavita Kane harps on the version of Mahabharata from another perspective. The doctor turned mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik, however has a different approach. He researches the stories and tries to find scientific justification in each act of a story. His seriousness in dealing with the myths can be witnessed in a brief episode of Mahabharata in his book Jaya.

According to his story, the Pandavas had a wonderful palace in a very beautiful city. As Duryodhana was walking carelessly in that palace, he fell into a pond which gave the illusion of hard surface at which Draupadi let out a peal of laughter and taunted him as ‘the blind son of blind parents.’ Duryodhana later took his revenge by disrobing Draupadi in the presence of her five husbands and all courtiers. From this episode, Pattanaik deduces that one should not make fun of one’s disabilities; something should be valued so much in these times. However, gods, god men, and their folklores continue to be an inspiration for authors since time immemorial.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *