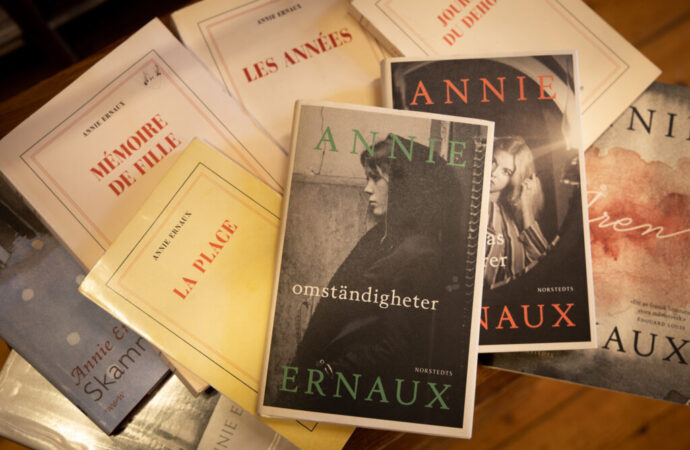

When I read Proust or Mauriac, I cannot believe they are writing about the time when my father was a child. In his case it was more like the Middle Ages – Annie Ernaux

After a long time, I cried heartily while reading a book after every five pages. Annie Ernaux’s ‘A Man’s Place’ is a lyrical ode of author for the memories of her father, his mannerisms, and her fractured love for him. Till the time I read this small book, I couldn’t imagine that how rational, poignant, and yet tranquil a memoir about a parent could be without any picturesque reminiscences and ironies. The book was first published in French in 1983 and then in English in 1992. The most striking aspect of this book is truthfulness with which the author had painted a subtle portrait of her father. Ernaux confesses in the book that she had tried writing a novel in which her father was primary character but she had felt towards middle that she had no right to narrate a life governed by necessity artistically. She adds further, “No lyrical reminiscences and no triumphant display of irony. This way of writing comes neutrally to me.”

The book begins with a regretful quote that suggests that writing is a primary recourse for those who have betrayed. The betrayal that appears to be in author’s mind is not understanding her father’s perspective who first worked as farmer, then rose the become a soldier, and then eventually became a grocery-shop owner. She also regrets her moving into a realm that was completely alien to him. She narrates truthfully that she was embarrassed of the fact that he couldn’t spell ‘read and approved’ once and finally settled for ‘read and a proved.’ This remorse however is a proof of her dedicated love for him as she narrates his laughing and his spending time in raising rabbits and chickens. The chasm in their relationship grew deeper when her lessons became incomprehensible to him and when she stopped talking to him after school. This appeared to me most a widespread idiosyncrasy of fathers and daughters in most of our families.

Ernaux’s most riveting account is in the beginning of the book where she describes her father’s death before she appears for an interview for the designation of a post-graduate teacher. She refers the cremation as the ‘obscene ceremony of all’ where the body ‘had to be wrapped in a plastic bag and dragged.’ The meticulous details of washing his body, planning an after burial party, lowering his coffin into grave, and her mother’s frozen face can put anyone to tears. The author professes, “I don’t remember the doctor who was called in to sign the death certificate. Within a few hours, my father’s face had changed beyond recognition.” At this juncture in the book, reading can became a personal experience for anyone who had faced all this.

As the story progresses, the author illustrates the life of a peasant in a blue-collar social class that begins from 1900s to mid-sixties. Her parents live through first world-war as teenagers, the economic crisis of 1929, the second world-war, and economic boom after it. In the process, she describes her transition from a daughter of a blue-collar worker to an intellectual bourgeoisie. At one instance, she writes that her husband never went to her home but admired the kindness of her parents whenever he went. He missed the lively banter and usage of allusions in conversations that happened in his family which I find strange if he was in love with his wife. After her father returns from the war, he started a grocery-cum-cafe store with her mother. The travails of their journey while her mother became in-charge of accounts and her father worked in oil-refinery at night are marvelously described by Ernaux.

As the author moved into adolescence, her mother became more important to her since she was more confident around people and they went to their favourite pastry-shop together. The author then moved to London and only her mother came to receive her at station. At this point, she confesses that there was nothing more to say or discuss with her father but she was sure of his affection for her in his absence too. In my opinion, all relations die in the absence of even fundamental understanding about hopes and aspirations of one individual by another. In this case, the author humbly takes all the blame on her. Afterwards, her father confined himself to his garden and his health deteriorated. He had developed a stomach polyp for which he kept blaming the food and took milk of magnesia. These moments of naivete are pure delight in this book.

Few other alluring moments in the book include her father welcoming her grandson for the first time with a haircut and her son innocently enquiring, ‘Mummy, why is the gentleman sleeping?’ while her father became incurably ill. She describes his death too very reflectively by saying that she was reading Les Mandarins by Simone de Beauvoir while he was about to die. It appeared a metaphor to me that was urging her to abandon her elite Mandarin status and to work for the poor which was similar to some situations in the renowned work. The business closed down after her father’s death and she took possession of the legacy that she had once left while she entered her educated bourgeois world. Hence, the book is a delicate and understated work for all those we love and for those who love us without an understanding of our beliefs and aspirations.