To immigrants and exiles everywhere, the uprooted, the re-rooted, the rootless, and to the trees we left behind, rooted in our memories! – Elif Shafak

Any contemporary book has not influenced me since the past two years as much as ‘The Island of Missing Trees.’ Long after I had completed this book, I kept thinking about the political upheavals in Cyprus, the personified fig tree, and its association with the family that had adopted it. The book is the moving account of Kostas and Defne Kazantzakis, a Greek and a Turk divided painfully in a postcolonial Cyprus rife with conflicts and the detriment caused to the natural world and immigrated families due to this. The skilfully spun plot presents a narrative on behalf of the fig tree planted at London home of Costas, who is grieving for his recently deceased wife, Daphne. His daughter Ada is also mourning for her mother and finds his affection for the tree absurd. Shafak divides her novel into sections such as roots, trunk, branches, and ecosystem reflecting the anatomy of a tree. Through this, she weaves the fig’s reflective narrative interwoven in past and present, creating an unforgettable reading experience.

The Welsh word hiraeth implies a deep longing for one’s homeland. It may be trees of a homeland for some such as me, while culinary delights for others, but the predicament of someone who cannot return to their homeland due to political strife is particularly unimaginable. In such a situation, both those who move away and stay bear the brunt. Shafak suggests that generational trauma of immigrants is unavoidable and can take the form of prolonged regret visible in many communities. In this book, every character suffers from that miasma of yearning for his or her homeland. In Costas, it is visible in the form of extraordinary care he renders to the fig tree which he brought from Cyprus while it acquires the form of several delectable Turkish delicacies and superstitions in Merriam. Ada knows nothing about Cypriot culture, which inflicts abrasion on her soul.

A British Major General Peter Young had drawn a border on the map that separated Greek from Turks. This line that separates Greeks from Turks is called the Green Line. This resulted in Nicosia being the only divided capital in the world. The fig tree reflects that if his hand had shaken even slightly, it would have changed the fate of her entire family. Remembering the strife at her home, she says, “We are scared of happiness, you see. From a tender age we have been taught that in the air, in the Etesian wind, an uncanny exchange is at work, so that for every morsel of contentment there will follow a morsel of suffering, for every peal of laughter there is a drop of tear ready to roll.”

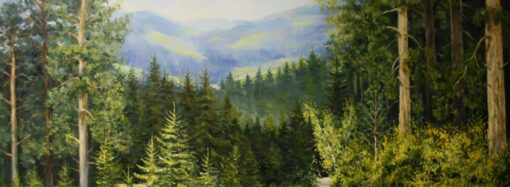

Given Shafak’s love for the natural world, this book is replete with fervent portrayals of green ecosystems of Cyprus. The author also seems to be inspired by the works of authors such as Robert Macfarlane and John Muir who dedicated their entire lives for preserving the wilderness. Each page throbs with assiduous details about the songbirds, mosquitoes, and butterflies. She revels in the wisdom of flowering horse chestnut trees and pine trees while surviving amidst harsh circumstances and illustrates like a botanist how trees can warn their neighbours about a danger by sending signals through an intricate network of latticed fungi buried in soil. Hence, each portion in the arboreal voice of the fig tree is delightfully enlightening.

The book presents a compelling discourse in favour of the sentience of trees challenging its readers to reconsider the sapiens-centric idea of time, ways to acquire knowledge, communicate, bear sufferings etc. All the while in the book, there appears to be a strange kind of communication between Costas and the fig tree. She says, “Arboreal-time is cyclical, recurrent, perennial; the past and the future breathe within this moment, and the present does not necessarily flow in one direction; instead it draws circles within circles, like the rings you find when you cut us down.”

Another remarkable trait of this book is the delineation of its characters. The account of a considerate botanist Costas, who felt more himself with trees and animals than with human beings, and his daughter who has no idea about her roots but mocks her aunt’s superstitions are simply unforgettable. Distraught with her misfortune, Merriam has built around herself a fragile universe of her superstitions, recipes, and proverbs. The plot spun around all these characters is both tender and heart-warming. I especially admired the account of the peripheral characters such as Yusef and Yiorgos and how their restaurant became a safe house for the love of Costas and Dafne. Another meditative moment in the book was the burying of the fig tree by Costas and Merriam, which demonstrated how deep its association with the family was. Lastly, the book is meant for those who can admire the gossamery details about the friendly messaging between fig and hawthorn trees, the diversity of butterflies, and the vulnerabilities of trees resulting in resilience in a perpetual ecosystem.