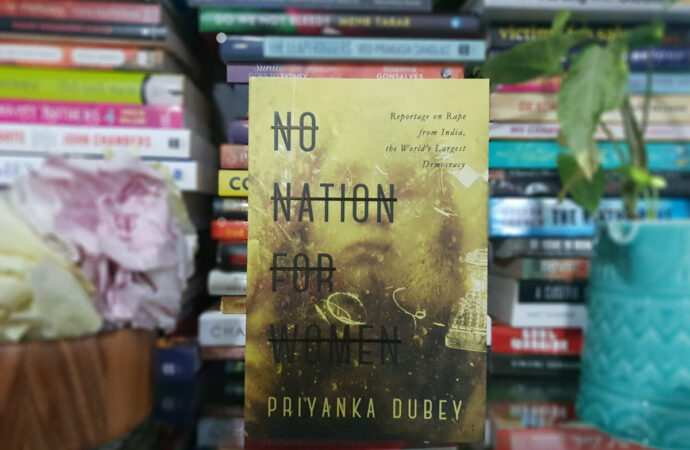

Priyanka Dubey in a candid conversation talks about types of rapes in India, constraints in reporting these, and her latest book ‘No Nation for Women.’

Q. According to a report of NCRB, four out of every ten of rape victims in India are minor girls. What does did represent about our society?

The diverse geography and demographics of India leads to various dimensions and facets of crimes against women in India. But, patriarchy is the nucleus of all these problems. The statistics by National Crimes Records Bureau (NCRB) of India says that 106(87 now) women are raped in India every day and four out of every ten women are minor girls. These appalling figures depict that the rape of a woman has nothing to do with her body or demeanour. It rather speaks of grotesque depravity endorsed by patriarchal beliefs in those men.

Q. How has our country evolved when it comes reporting of sexual abuse or rape?

The increase in number of crime definitely suggests that more women are reporting rape now. But speaking up against sexual abuse still remains a stigma in our country. Most of the women don’t opt for reporting of these crimes because of prevalence of victim-shaming attitude in India. The imposed concept of body purity for women which snowballs into unbearable shame and stigma in case of the sexual assault.

Reporting of sexual crimes is further exacerbated by absence of police stations in far-flung areas and absence of gender sensitization among police forces. Furthermore, policemen often fail to prepare a foolproof FIR which may delay the process of filing a charge-sheet. As a result of these loopholes, accused have sufficient time to get an anticipatory bail. The circumstantial evidence can also be destroyed in this span of time.

Q. It is very unfortunate that instances of corrective rapes like that of Kalabai, Rohini, and Kamyani are rampant in India. Are fault lines in judicial system or ineffective police administration responsible for it?

It is lacunae in both and in other peripheral systems that leaves a victim helpless as I have stated earlier. In most of the cases which I reported, investigations were not carried further despite of a filed FIR. Afterwards, loopholes in investigative process such as doctors who may not have prepared medical reports, witnesses who may have turned hostile, and defence lawyers which highlighted contradictions led to benefit of doubt for the accused. Hence, systemic troubles assert themselves everywhere.

Q. Your book has some interesting findings about political rapes in Tripura. Why do you think crimes against women are so high in this far-flung north-eastern state?

North-east is a region with diverse topography and cultural ethnicities. For mainstream media and its audience, it appears like a different realm. Therefore, more reporting by local reporters is required from the ground zero. A 50 years old Tripuri woman from Hrangkhawl tribe told me that rapes in Tripura happen due to political witch -hunting. She was raped by a CPI (M) cadre man because she had dared to join BJP. According to official government figures, the rate of crime against women in Tripura is 68.2 percent. In addition to this, a women’s rights lawyer told me that the cadre of left is everywhere and there is little tolerance towards female candidates of other parties.

Q. Is casteism also one of the major reasons behind molestation and rapes as told in account of Bhagana rape case where 2,000 out of 3,800 voters are Jats?

Casteism was main precursor of Bhagana rape case. A dalit sarpanch in Bhagana rape case in 2011 decided to distribute 280 square yards of village land among villagers. Thereafter, a new jat sarpanch distributed the land in proportion to ownership of land. This left dalit families landless. As dalits protestedto this, jats retaliated. According to elder sister of victims, the jats did this to those girls because they were retaliating against their fight for the village land and playground. Furthermore, the chief public prosecutor of Damoh, Rakesh Shukla had told me, ‘Out here, an upper caste man’s fragile sense of self gets threatened if a girl dares defy him; he must retaliate! And he does.’

Q. What according to you is state of affairs of human trafficking after Justice Verma Committee dedicated a whole chapter to women trafficking in Criminal Amendment Act, 2013?

In the aftermath of December 2012 Delhi gang-rape, the ‘Justice Verma Committee’ was formed which dedicated a whole chapter to women trafficking in its recommendations. It is a comprehensive pro-women and pro-humanity report. On the recommendations of the Justice Verma Committee, Section 370 of IPC was amended and Section 370 A that defined human trafficking was added in it. But, these recommendations are yet to be followed in letter and spirit. I found this in ten villages of Lakhimpur where almost every village has its share of stories where girls went to Delhi and never returned.

Q. Were the combined bench of Justice R.M. Lodha and Justice Madan B. Lokur of the Supreme Court of India and events in the aftermath of it able to pave a concrete way for the rehabilitation of rape victims?

Ironically, just one scheme (not law) exists for the rehabilitation of rape victims in India. In 2005, the NCW came up with a ‘Scheme for Rehabilitation and Relief of Victims of Rape, 2005’. The Commission proposed directives to the Ministry of Home Affairs for rape survivors, which included legal help, shelter, and vocational training for victims of such crimes. But, the Indian judiciary is still far away from developing an effective compensatory and rehabilitative justice model for rape victims. The most important thing is until we segregate the idea of body purity to a woman’s existence; we would continue to make every woman vulnerable.

Q. How would you describe your emotional journey from collecting reportages to meeting rape victims in person across various states of India? Did you experience meltdown at any moment during the journey?

It was seven years of dark journey. I broke down several times during this journey while I met and discussed ordeals of victims through their voice. This bruised my soul to a large extent. I clearly remember that I had folders related to all kinds of rape of thirteen chapters on my laptop. Each chapter, recorded voice clip, and reporting trip altered some aspect of personality in me. During the course of this process, I kept slipping in and out of darkness. But, these journeys imbibed in me confidence, courage, and infinite compassion which became a refuge for my vulnerable self.

About the author: Priyanka has won multiple international and national accolades for reporting on social justice and human rights. This includes 2012 Press Council of India’s Award for Excellence in Investigative Journalism and the 2011 Ramnath Goenka Award for Excellence in Indian Journalism. She is from Bhopal and this is her first book.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *