The book describes the journey of a fervent orphan Jane who gradually metamorphoses into a benevolent, sensitive, and an independent young woman.

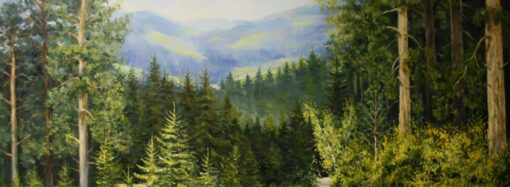

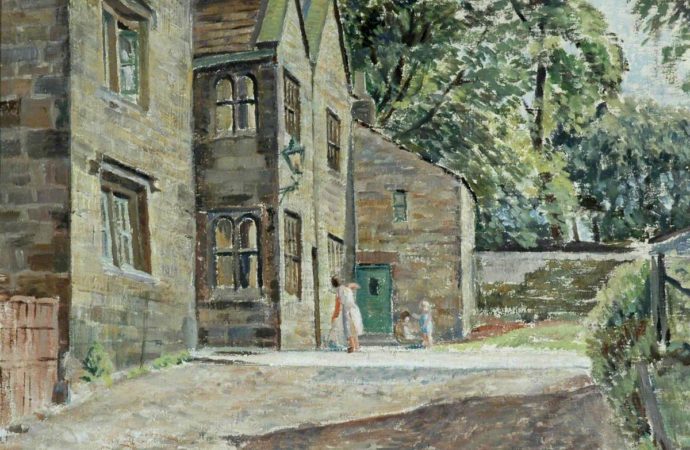

A classic like Jane Eyre(1847) is so engraved in memories of my adolescence that I could barely think about it critically. Despite its widely acclaimed criticism about treating Bertha Mason as a nondescript entity and in spite of reading its prequel Wide Sargasso Sea before, I always find myself lost in its shrubbery. The tall as trees hollyhocks, lilies, and sweetbriars of Lowood and sturdy low-growing hazel and hawthorn bushes of Thornfield touch various responsive notes in me. The book describes the journey of a fervent orphan Jane who gradually metamorphoses into a benevolent, sensitive, and an independent young woman. The narrator’s character, self-esteem, and sense of self is shaped in the crucible of three worlds namely Lowood, Thornfield, and Moor House. “And now the vegetation matured with vigour; Lowood shook loose its tresses; it became all green, all flowery; its great elm, ash, and oak skeletons were restored to majestic life”, says narrator while recounting advancing of May at Lowood.

Without being professedly didactic, Charlotte Brontë’s intention (among other things) is to depict how intellect and unswerving integrity may win their way, although being oppressed initially by other predominating influences in society. The author serves all which a reader requires; perception of characters and power of delineating it, picturesque style, passion, and philosophy of life. From the first page to the last, it is imprinted with the same vitality. The minuteness of details in every chapter is also praiseworthy. Often there are strokes of great eloquence and their effect is unforced yet prevailing. The sentences such as ‘the great horse chestnut at the bottom of the orchard had been struck by lightning in the night, and half of it split away’ symbolise the fragility of life and induces a magical entrancement for the plot in me.

Talking about remarkable characters, Mr. Rochestor the owner of Thornfield manor and the guardian of Adele Varens whom Jane taught as governess is unforgettable. He is mysterious, assertive, cordial with servants, and a wanderer in relationships as he professes to Jane once that Adele’s mother Celien Varens was his grande passion. In the initial chapters, he appears to have encountered something irrevocable when he tells Jane, “I envy you, your peace of mind, your clean conscience, your unpolluted memory. Little girl, a memory without blot or contamination must be an exquisite treasure – an inexhaustible source of pure refreshment: is it not?” As the plot progresses, he becomes increasingly playful with Jane to break her quiescence and to ascertain her sentiments about him.

The chapters when he dresses up as a gipsy fortune teller and summons Jane to library; when he feigns a prospective marriage with Blanche Ingram; and when he throws unwarranted questions at Jane about John Rivers make him an alluring lover. On the contrary, St. John Rivers is kind, icy, and inconspicuously sinister pastor. As an evangelist preacher, he earlier personifies the Christian doctrine of kindness and tolerance by allowing Jane to live at Moor House but becomes vindictive when she denies prospects of marriage with him. Miss Temple as a maternal figure and Sarah Burns as an intimate companion of narrator who helps her to endure grim days at Lowood are also significant. Bertha Mason, the first wife of Mr Rochestor, constantly asserts her existence by her threatening gothic laughter. It is easy to notice her husband’s lack of sympathy towards her mental illness which was rampant in 19th century England.

The Lowood chapters in the book are most terrifying boarding school story ever written. Girls there were persecuted, companion less, and malnourished being fed with burned porridge. But, Jane acclimatised to it gradually thinking about her predicament at Gateshead Hall with Mrs. Reed. According to her, life at Lowood was uniform but not unhappy. Excellent education provided at the institute then became her raison d’etre and fondness for some subjects her relentless pursuit. I wept with the narrator in the chapters where she describes her moral degradation blended with physical suffering after leaving Thornfield. “The first was a page so heavenly sweet-so deadly sad- that to read one line of it would dissolve my courage and break down my energy. The last was awful blank: something like the world when deluge was gone by”, confesses Jane while walking in the opposite direction of Millcote.

Reading this classic in my mid-thirties, I now feel that the romance between Jane and Mr. Rochestor is archetypal. However, it is more sympathetic and spiritual in its own way as compared to the impulsive and uncouth affection of Heathcliff and Cathy in Wuthering Heights. Also, the long drawn out self-righteous dialogues between Jane and Rochestor are weary to an extent. Whatever shortcomings may be hurled at the book, no one can affirm that it is weak or vapid. The sentences are devoid of literary allegories but still are skilfully spun. We hear nothing of Madame Maradan and the scenes are not staged in Belgrave or Grosvenor Square. The only fragrance that we come across is scent of a garden flower, or the odour of Mr Rochestor’s cigar. The plot finishes and the book ends but its magic doesn’t cease. This gives the book its charm, the narrator’s soul speaking to the reader’s soul.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *