Dr. Pankaj Jha, author of ‘A Political History of Literature’ speaks to Gunjan Joshi about the three treatises mentioned in his book namely Likhanavali, Kirttilata, and Purusapariksa.

Q. Mithila is known to be the land of saint Yajnavalkya, saint Gautam, and saint Kapil Muni. How do you view evolution of literature from ancient Mithila to 15th century?

Vidyapati lived in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. There is little traceable ‘continuity’ between the mytho-historical times of Mithila’s history (to which Yajnavalkya, Gautam etc. belonged) and the temporally verifiable times (13th century onwards to which Vidyapati belonged.) Nothing in the works attributed to these sages indicate that they were native to Mithila, notwithstanding the popular traditions associating them with this region. However, the breadth of Vidyapati’s compositions indicate that he was deeply conversant in the classical traditions of Sanskrit dharmashastric literature, also known as smriti literature. To the aforementioned sages, one smriti text is attributed to each. Vidyapati did refer to each of these smriti texts in his own dharmashastra and Vibhagasara. But, he also referred to several other dharmashastras with equal or greater frequency. In other words, Vidyapati’s literary and scholarly antecedents were not confined to those associated with the mythic antiquity of Mithila.

Q. Why did you choose Vidyapati to elucidate the literature of fifteenth century in India?

My choice of Vidyapati was determined by four overlapping factors. Firstly, I noticed that even though there was an enormous archive of Sanskrit, Apabhransha and ‘vernacular’ compositions available for the period of so-called Muslim rule but historians with very few exceptions, rarely paid attention to them and focused almost exclusively on Persian ‘sources’. Secondly, while there was a lot of research done on the heyday of Delhi Sultanate (13th – 14th centuries) and of Mughals (16th – 17th centuries), fifteenth century received very little scholarly attention. The third reason was while Bihar was often at the centre of historical narratives in ancient period (with reference to Buddha, Mahavira, Magadh, etc.) and came in focus again during anti-colonial struggles (with reference to Champaran, Sahajanand Saraswati, Jay Prakash Narayan etc), it was rarely highlighted in the medieval histories of north India.

Further, medieval historians remain focused on historical chronicles like those of Minhaj Jujzani, Zia Barani, Abul Fazl, etc. They turned to imaginative literature only for purposes of writing about bhakti ‘movement’, Sufism, and the likes. This gave rise to two parallel and water tight compartments of political history and cultural history. Focusing on Vidyapati helped me respond positively to each of these desiderata. He lived in the fifteenth century Mithila (present day north Bihar) and wrote in three different languages and several genres. His compositions span a vast number of themes including culture, law, ritual, love, tantricism, documentation, masculinity, and politics.

Q. What is remarkable about the three treatises of Vidyapati namely Likhanavali, Kirttilata, and Purusapariksa?

Fifteenth century witnessed extraordinary efflorescence in literary activities. On one hand, it was in terms of varieties of texts, themes and genres while on other hand it was about the rapid growth of a multilingual literary culture. My choice of these three texts (more than a dozen from which are attributed to Vidyapati) was dictated, primarily because of the diversity it offered. Likhanavali is a treatise on writing or documentation. Kirttilata is a political biography. Purushapariksha is a text on political ethics and masculinity for a man. The language of Kirttilata was Avahattha while the other two are in Sanskrit. Each of these texts has starkly different subjects. Yet all three of them help to overcome the political and the literary-cultural divide during that period. Thus, focusing on these texts helped me not only to write a political history of literature, but also gave me a chance to explore multi-linguality, masculinity and documentation of issues related to state and law.

Q. How do you view evolution of language from Sanskrit to Maithili during fifteenth century?

Again, there is no linear evolution of language from Sanskrit to Maithili. Maithili probably owes as much to Prakrit, Apabhransha and Persian as it does to Sanskrit. The local speech practice that eventually came to be known as Maithili had probably been in use in these regions long before Vidyapati started composing songs in that language. I must say I find it curious that Maithili users today like the users of other New Indo-Aryan languages are keen to associate themselves with (and find the origin of their language in) Sanskrit. The early Sanskrit theoreticians like Bhamah and Dandin and a host of other scholars until the eleventh century, clearly looked down upon these languages and did not deem them fit to compose literary texts in. The Sanskrit pundits thought of these languages as corrupt and this is evident in the way they described it. They used a generic term, Apabhransha which literally means ‘corrupt’ for these languages. It is very much possible that these dialects were as old as, if not older than, Sanskrit itself but we do not have any evidence since literary compositions in these languages start appearing only from roughly about eleventh-twelfth centuries.

Q. Any remarks about ‘Avahatta’, the language of Kirttilata. How is it related to Apabhramsha?

Apabhransha and Avahattha are usually considered to be synonyms. These are definitely connected and even in the middle ages some people saw them as hardly different. However, closer examination suggest that Avahattha was probably the word used to describe more recent form of Apabhransha that showed a larger number of both tatsam (Sanskrit words imported as it is) and Persian words. Abdul Rahman composed his Sandesharasak in Avahattha a century before Vidyapati composed his Kirttilata.

Q. What was the impact of Bhakti movement on the literature of fifteenth century?

The literary currents that are generically described as ‘bhakti corpus’ in north India were too varied and vast, and most of them were composed in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Hence, there is predictable overlap between the two categories. However, a large chunk of the compositions of the fifteenth century can by no stretch of imagination be labeled as bhakti literature. Usually these texts talk about law, non-devotional eroticism, political ethics, geographical treatises, ritual digests, and so on. Ramchandra Shukla’s scheme of classifying medieval north Indian literature into stages of adikal, bhaktikal, ritikal, and adhunik kal itself needs to be questioned.

After all, Vidyapati is also famous for composing erotica that rightly or wrongly was associated with ritikal which according to Shukla has its advent in seventeenth century. In other words, it is difficult to say what impact bhakti movement had on the fifteenth century when Shukla’s scheme of classification itself is open to question. In addition to this, the fifteenth century literary corpus demonstrates variety of themes, genres, languages and linguistic registers. Hence, you tend to realize that bhakti can only be understood as a focal point of devotionalism. I don’t find any similarity in the literary styles of Kabir and Tulsi or Chandidas and Surdas. Therefore, bhakti cannot be reduced to either ideological singularity or an identifiable pattern of literary style which is why there is no way you can measure its impact on literary archive of any century.

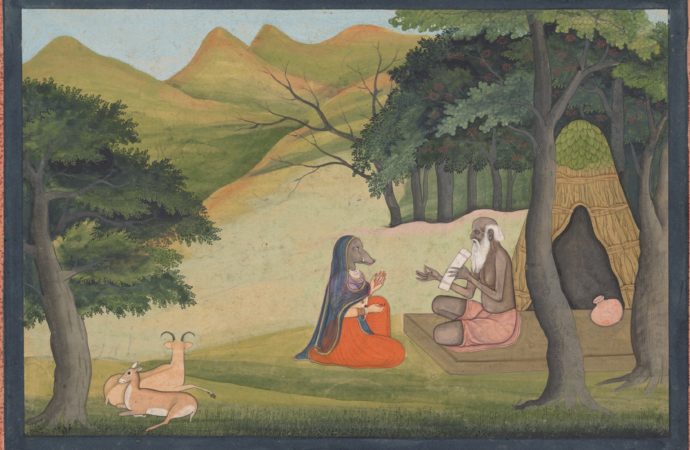

Q. Do you think Puruspariksha places purusa or men above women in the realm of Niti or politics?

I would go a little further and say that Purusapariksha portrays politics as a sport played only by men. In Purusapariksha, the brahmana scholar of Mithila claims that he is composing a text on naya, i.e. niti (literally, political ethics). However, he structures it as a collection of stories or a katha. In this katha, he narrates the characteristics to identify an ideal man or a purusa and what are the qualities to be expected in such men. It is interesting that the word purusartha in Sanskrit connotes the four objects of life namely dharma, artha, moksha and kam. On the other hand, purusartha itself etymologically means the ‘aim of a man’s life’. Let’s not forget that the word purusa used here is not gender-neutral, its opposite is stree. Vidyapati himself marked this contrast unambiguously as he remarks in the book that lions and real men fend for themselves, while children, women and cowards are dependent on others. There are dozens of such statements in Purusapariksha that make it clear that when it came to politics, Vidyapati gave no scope to women. It is another matter that many of the stories that Vidyapati relates in this very text might be read to recover agency on the part of the women but that is not how the brahman author seems to have seen it.

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *